Todd A

pfm Member

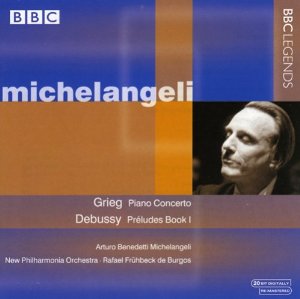

Yep, I do immensely enjoy the Grieg Piano Concerto. Always have. Start to finish, it delights, but the slow movement and the slow section of the finale just gets me every single time I listen, at least in better performances. Over the years, I’ve read some disparaging remarks about the work, and a few people seem to not hold it in the highest regard. Maybe this has to do with its comparative popularity – how can something that is popular be good? – but maybe not. That doesn’t matter, either way. When I look at available recordings, I see that many titans of the piano have recorded it, some multiple times. It’s this fact that contributes to me liking it so. When I can listen to Michelangeli and then Freire and then Andsnes, well, what’s not to love? I decided it was time to systematically work my way through this work to find the greatest recording. Well, sort of. Since I first heard it, Leif Ove Andsnes’ second recording with Mariss Jansons has stood as my favorite. So really, this exercise in musical excess will determine if that recording holds up against the onslaught.

Note that only the final version of the concerto will be surveyed, so Love Derwinger’s recording of the original version will not be included. Also not included is Robert Riefling’s recording because I have not made it a point to buy an LP copy and also because whichever entity owns the Valois catalog is committing a crime against humanity by not issuing all of his LP era recordings.

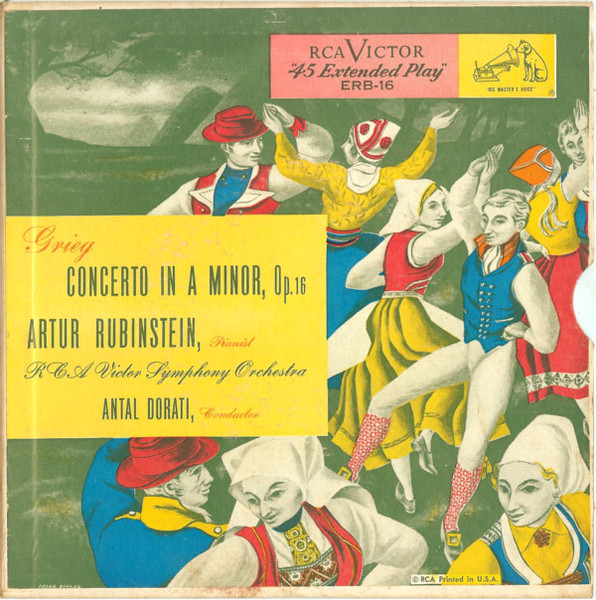

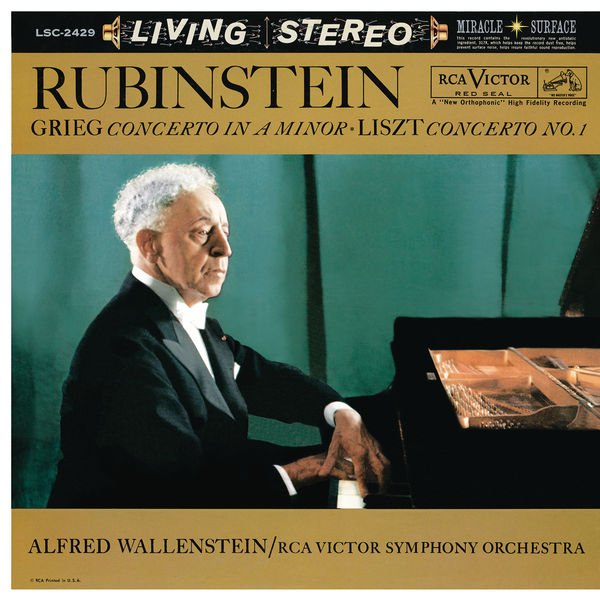

What better way to start out than with not one, not two, not three, but four recordings by Arthur Rubinstein?

First, the 1942 recording with Eugene Ormandy and the Phillies. Tight timps launch the work, Rubinstein forcefully announces his presence, the band responds, then Rubinstein comes back, all big chords, then jaunty playing. Then finally the hypnotically beautiful tunes arrive. Both band and soloist go back and forth, and the middle-aged soloist zips through many of the passages. Ormandy makes sure to let the strings luxuriate, and one hears some old world portamento and style. The cadenza has a free-wheeling sound to it, which it should since it is essentially live. The second movement sounds very beautiful, but also pretty quick, with Rubinstein, in particular, not going slow anywhere. The finale starts extra zippy before backing off to those gorgeous melodies, and here Rubinstein heaps on the beautiful playing. The final two-thirds or so is all zippy, high-energy, high drama playing.

Note that only the final version of the concerto will be surveyed, so Love Derwinger’s recording of the original version will not be included. Also not included is Robert Riefling’s recording because I have not made it a point to buy an LP copy and also because whichever entity owns the Valois catalog is committing a crime against humanity by not issuing all of his LP era recordings.

What better way to start out than with not one, not two, not three, but four recordings by Arthur Rubinstein?

First, the 1942 recording with Eugene Ormandy and the Phillies. Tight timps launch the work, Rubinstein forcefully announces his presence, the band responds, then Rubinstein comes back, all big chords, then jaunty playing. Then finally the hypnotically beautiful tunes arrive. Both band and soloist go back and forth, and the middle-aged soloist zips through many of the passages. Ormandy makes sure to let the strings luxuriate, and one hears some old world portamento and style. The cadenza has a free-wheeling sound to it, which it should since it is essentially live. The second movement sounds very beautiful, but also pretty quick, with Rubinstein, in particular, not going slow anywhere. The finale starts extra zippy before backing off to those gorgeous melodies, and here Rubinstein heaps on the beautiful playing. The final two-thirds or so is all zippy, high-energy, high drama playing.