Todd A

pfm Member

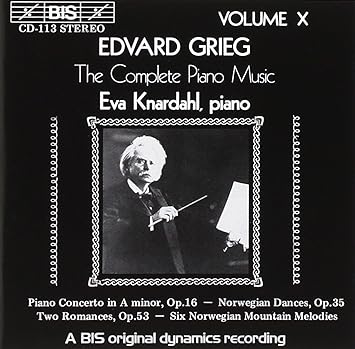

Eva Knardahl with Kjell Ingebretsen and the Royal Philharmonic. It’s a BIS original dynamics recording! The slow first movement starts with crisp timps and broad, large-scaled playing from Knardahl. Knardahl doesn’t even bother trying to play in an especially virtuosic manner, instead preferring to play more slowly and let the music breathe. That’s not to say she’s not up to snuff, because the cadenza, for instance, is quite good, but this is not a barn-storming version, very much on purpose. Her use of a Bösendorfer brings brighter upper registers and weightier lower registers, which blends very well with her style. The Adagio starts with lovely orchestral playing with especially attractive string playing. Knardhal shines, coaxing beautiful playing out of her instrument and taking her sweet time doing it, and she happily takes on an almost obbligato approach in some passages. This is about musical flow and beauty, not super-heated intensity, and those bright upper register trills sound just nifty. The finale is a bit slow, though here Knardhal plays some passages at a nice velocity, though with reduced volume. There’s a comparatively relaxed feel to the whole thing, with only the hardest hitting tuttis sounding intense. This is how to do a slow take on the concerto. Not one of the greats, but excellent for what it is.