Todd A

pfm Member

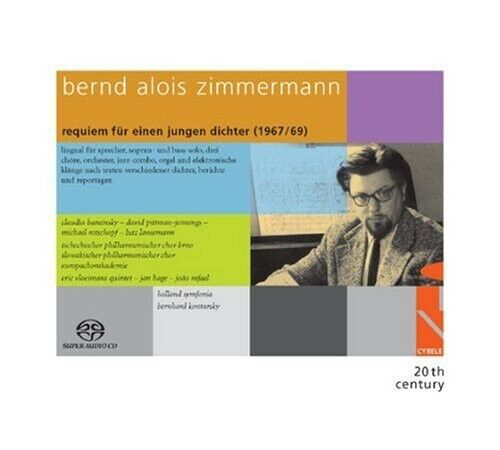

If you’re gonna do modern Requiems, you might as well make sure BAZ gets in the mix nice and early. Requiem für einen jungen Dichter is Zimmermann at his most Zimmermannian. The work is gigantic, for two speakers, two soloists, three choirs (because yes), jazz band, organ, accordion, tape, orchestra, and kitchen sink. It combines the Latin mass and multiple texts. This recording was released in surround sound, to approximate what a proper avant-garde staging should sound like. I listen through stereos and stereo headphones only, so I did not get the whole aural experience.

Now, I have listened to my share of hodge-podge avant-garde nonsense, where music sometimes is comprised of noise, some new music, and a pastiche of others’ compositions, and often it sucks. BAZ, though, more than even Berio or Schnittke, has got my number. Why that is, I just don’t know. The work unfolds as pure chaos, moving beyond aleatoric music to something seemingly nihilistic and pointless, yet very serious and pointed. As tracked here, the first movement is nearly forty minutes. What happens in it? Well, nothing and everything. It’s an experience, not music. It’s like some little snippets from Sgt Pepper’s blown up to something massively scaled. And as it happens, The Beatles make their appearance in the piece. Imagine a swirl of sound and chaos where bits of Tristan emerge and fade and so does Hitler. The musical borrowings are extensive, the literary ones highest of highbrow. It’s all terribly pretentious and overbearing and ridiculous and daffy – and all-consumingly bewitching. Seriously, I have no idea how BAZ does it.

Now, this is most definitely not a piece to listen to frequently. This is a once every five-to-ten-year kind of work. But Michael Gielen believed in it enough to record it twice, and Gary Bertini recorded it once. I will listen again, and I doubt I wait five years. António Pinho Vargas’ Requiem is far more musically satisfying, and is a piece that deserves more attention, but this makes a great and very, very different follow-up. As mentioned before, this work is an experience, one I am most glad to have had, and one I will have again.