Todd A

pfm Member

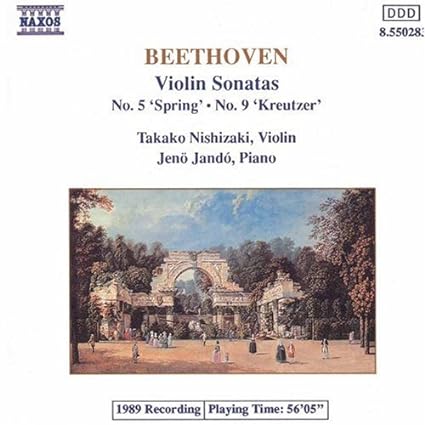

Takako Nishizaki and Jenő Jandó. Nishizaki starts conventionally in the Adagio sostenuto, but she generates a small sound, which becomes more evident after Jandó joins and they play together. He often just drowns her out, without seeming to try. The musical approach is unfussy, straight-forward, and good enough for a library recording if one just wants to have the work. The Andante sounds like a slower, properly varied style approach, while the Presto has nice enough pep and drive. If the description sounds lackluster, it's because the playing falls into the completely competent but more than kind of dull category. Sub-par early Naxos sound doesn't help. Meh.