Todd A

pfm Member

Wolf

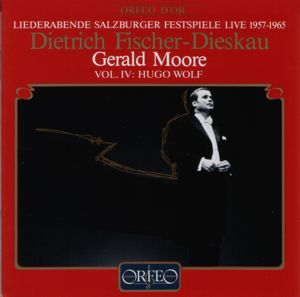

Ive sampled a variety of lieder by a number of composers over the years, but until this disc I never got around to listening to the songs of Hugo Wolf. So when I stumbled on this old disc of an even older recital by that estimable duo of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Gerald Moore I figured it was time. The disc contains a recital from 1961 and has 20 of Wolfs Mörike lieder, all penned in 1888. On the evidence of this recital, I really need to investigate more of Wolfs music.

As I expected, Fischer-Dieskau and Moore work perfectly together, with Moore generally supplying the steady base from which Fischer-Dieskau can launch into interpretive flights of fancy. Many of the songs have a dark or somewhat dark mien, and they sound unusually rich. The texts are all quite good, and some more than that. And sometimes its the smaller works that hit hardest. For instance, Bei einer Trauung is extremely brief, yet its unsettling piano part and condensed verse describing an unhappy wedding packs a wallop. There are a number of other similar moments through the disc, and Fischer-Dieskau digs in. His mannerisms do show through here and there, and he is histrionic in the last two works in the recital (Zur Warnung and Abschied), so those who do not like him probably wouldnt like this disc. Me, I do, and need to hear more.

Sound is definitely not modern: it sounds like a live recital recording from its time and the volume and scale of both singer and pianist varies a bit more than one would ideally prefer.

Ive sampled a variety of lieder by a number of composers over the years, but until this disc I never got around to listening to the songs of Hugo Wolf. So when I stumbled on this old disc of an even older recital by that estimable duo of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Gerald Moore I figured it was time. The disc contains a recital from 1961 and has 20 of Wolfs Mörike lieder, all penned in 1888. On the evidence of this recital, I really need to investigate more of Wolfs music.

As I expected, Fischer-Dieskau and Moore work perfectly together, with Moore generally supplying the steady base from which Fischer-Dieskau can launch into interpretive flights of fancy. Many of the songs have a dark or somewhat dark mien, and they sound unusually rich. The texts are all quite good, and some more than that. And sometimes its the smaller works that hit hardest. For instance, Bei einer Trauung is extremely brief, yet its unsettling piano part and condensed verse describing an unhappy wedding packs a wallop. There are a number of other similar moments through the disc, and Fischer-Dieskau digs in. His mannerisms do show through here and there, and he is histrionic in the last two works in the recital (Zur Warnung and Abschied), so those who do not like him probably wouldnt like this disc. Me, I do, and need to hear more.

Sound is definitely not modern: it sounds like a live recital recording from its time and the volume and scale of both singer and pianist varies a bit more than one would ideally prefer.