Todd A

pfm Member

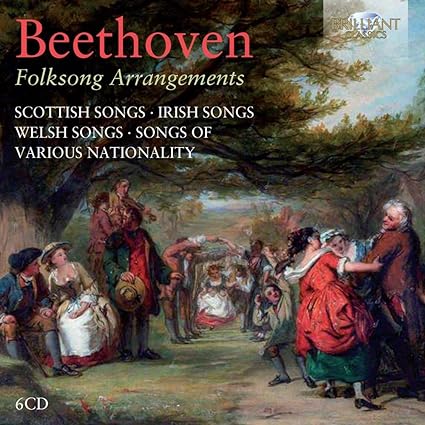

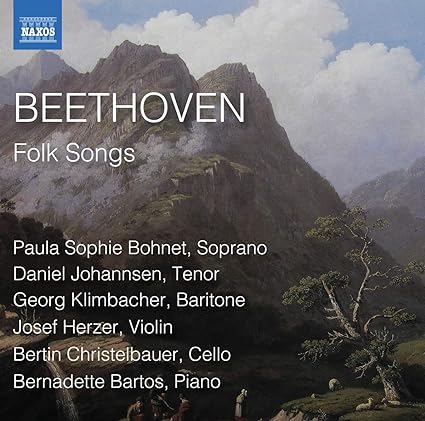

These seven discs represent one of the main draws of the Naxos Beethoven edition. Here are seven discs spread across two releases that I likely would never have purchased otherwise. I have a reasonably nice collection of art songs, but it is dominated first by Schubert (very rightly so), and then by various French composers (also rightly so). Until this set, I had acquired only a handful of Beethoven songs sung by Heinrich Schlusnus in one volume of the prior DG Beethoven Edition, which was purchased expressly for the Annie Fischer and Ferenc Fricay recording of the C Minor concerto, and only one measly complete disc of Beethoven songs from the L'Oiseau-Lyre classical era big-box which was purchased expressly for the Malcolm Binns sonata cycle. (Those evil transnational corporations literally forced me to buy a doorstop box. I may never forgive the shifty execs who ran the company at the time.) For this collection, even Mr Heymann didn't opt to commission all new recordings, instead opting to license a blob of them from Brilliant Classics. (And another blob from Capriccio, coming later.) Whatever works.

Anyway, there are too many small songs spread across too many discs to really do an in-depth summation. Rather, I can just report that Beethoven, author of some of the most radical and revolutionary music, music that smashed the strictures and limits of forms of the day in works like Op 55, and the visionary genius who pointed the way to the future in works like Op 131 while transcending feeble human limits of musical expression, also penned nifty, tuneful miniatures. Having not listened to pretty much any of these works, and not reading any liner notes or anything online, I came in expecting serious and weighty songs for piano and vocalist, but instead I was greeted by something novel - and not coronavirus: Beethoven set his renditions of folk tunes mostly for soloist and piano trio. How about that? And wouldn't you know - and really you should - the combination works splendidly. Beethoven provides lovely support from the piano, but the strings add an additional lightness, an additional sweetness in places, and an additional sense of subdued prankishness in places. The tunefulness approaches Schubertian goodness in places, too. The music is unmistakably Beethoven's, as some common figurations, phrasing, key choices, and so forth make their appearance, but it is lighter, funner Beethoven. And how great is it to hear Beethoven's music supporting English texts, very ably sung and very easily understandable on top of all of that, including a proper setting of Auld Lang Syne? It's pretty freakin' great, that's how great it is.

Recordings involve many artists over decades, so sound quality varies, but that's perfectly fine. Here's a big chunk of music that justifies the purchase all by itself.