Todd A

pfm Member

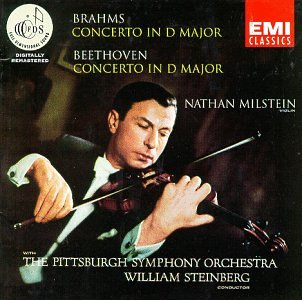

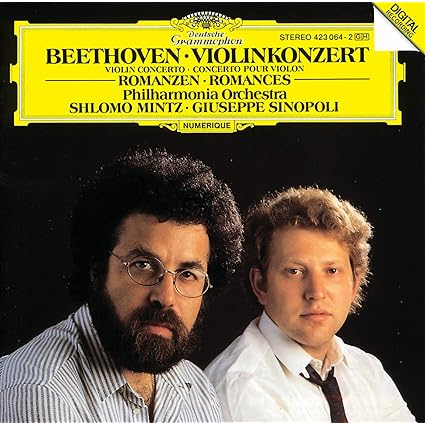

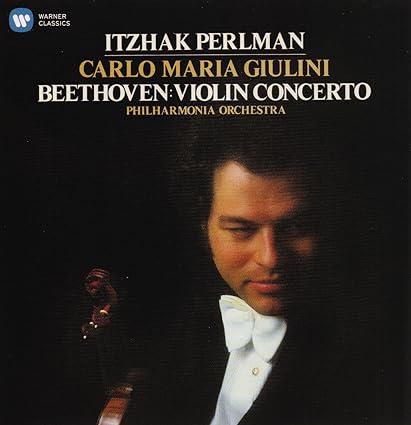

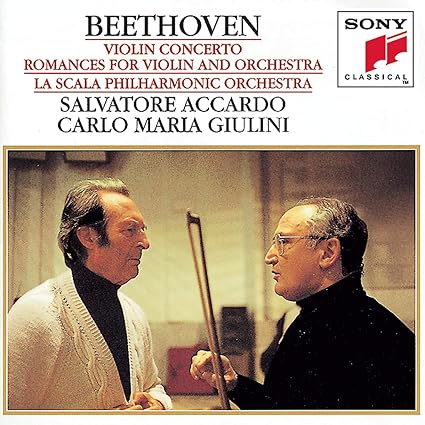

For this Beethoven year, I decided to systematically listen to all recordings of the Violin Concerto in my collection and to snap up some recordings that I had, inexplicably given my collecting proclivities, not yet acquired. This is not Lou's best concerto effort (that's the Emperor), nor is it the pinnacle of the Violin Concerto repertoire (that would be the Sibelius), but it's pretty nifty, and in a great performance, it's a crackerjack work. Now, starting in on this shootout, I'll just mention that my long-standing favorite is from the incomparable Ferras/Fluffy pairing, so that will come last, to hear if it holds up.

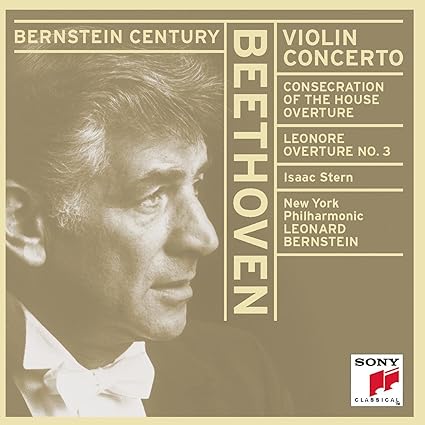

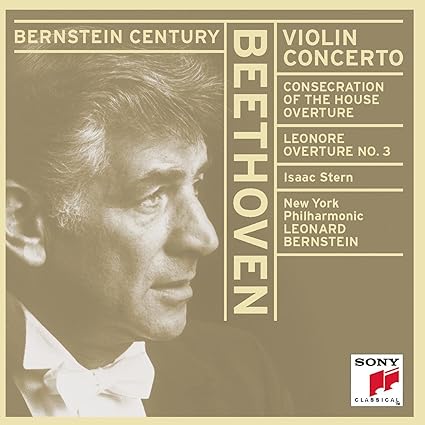

I started with one of the first recordings of the work I heard: Isaac Stern paired with Leonard Bernstein. In the Allegro ma non troppo, Bernstein and the New Yorkers start things off nicely, with decent weight and admirable control, with Lenny opting for sensible tempi. Stern sounds fairly light, small, and thin, and Lenny scales back for him. A couple obvious edits pop out, as one expects with this violinist, and the cadenza is slow, weak, at times unsteady, and boring. The aged sound cannot be avoided, and in the tuttis one can hear increased hiss level, at least in The Bernstein Edition release, indicating some mixing desk tomfoolery. In the Larghetto, Lenny and crew again lay down fine support, and Stern fares comparatively better here. The movement is small of scale and leisurely, and sounds reasonably nice, I guess. The famous duo close out with a Rondo of more or less sufficient pep, though again Stern sort of bores, though his cadenza, very obviously pasted together from multiple sessions and with obvious level manipulation, is a bit better than in the opening movement. A good amount goes missing. One good thing about shootouts is that one can root out duds. I will never listen to this recording again.

I started with one of the first recordings of the work I heard: Isaac Stern paired with Leonard Bernstein. In the Allegro ma non troppo, Bernstein and the New Yorkers start things off nicely, with decent weight and admirable control, with Lenny opting for sensible tempi. Stern sounds fairly light, small, and thin, and Lenny scales back for him. A couple obvious edits pop out, as one expects with this violinist, and the cadenza is slow, weak, at times unsteady, and boring. The aged sound cannot be avoided, and in the tuttis one can hear increased hiss level, at least in The Bernstein Edition release, indicating some mixing desk tomfoolery. In the Larghetto, Lenny and crew again lay down fine support, and Stern fares comparatively better here. The movement is small of scale and leisurely, and sounds reasonably nice, I guess. The famous duo close out with a Rondo of more or less sufficient pep, though again Stern sort of bores, though his cadenza, very obviously pasted together from multiple sessions and with obvious level manipulation, is a bit better than in the opening movement. A good amount goes missing. One good thing about shootouts is that one can root out duds. I will never listen to this recording again.